ASRA Carl Koller Memorial Research Grant 2016: NMDA Antagonists and Steroids for the Prevention of Persisting Postsurgical Pain After Thoracoscopic Surgeries: A Randomized Controlled, Factorial Design, International, Multicenter Pilot Study

Study Acronym: Preventing pAIn with NMDA antagonists—Steroids in Thoracoscopic lObectomy Procedures (PAIN-STOP) Pilot Trial

The Carl Koller Memorial Research Grant supports research projects that enhance patient care by improving our understanding and delivery of regional analgesia and pain medicine interventions. This research funding goes a long way in promoting research endeavors from ASRA members within North America. As a recipient of this award for 2016, I would like to express my sincere appreciation and gratitude for the ASRA research committee and the Board of Directors. For a clinician researcher like me, it is a great encouragement and motivation to continue to engage in meaningful research work and bring value to clinical care. As it is also an acknowledgment of the importance of our research project, I would like to highlight its background, interventions, and significance, apart from a study update as of September 2017.

“The Carl Koller Memorial Research Grant supports research projects that enhance patient care by improving our understanding and delivery of regional analgesia and pain medicine interventions.”

Background

Persistent postsurgical pain (PPSP), which develops or increases after a surgical procedure, affects 10–50% of the surgical population[1] and has been recognized as a health priority. Thoracic surgeries have a high risk of PPSP, affecting 25–60% of patients.[2] Although video-assisted thoracic surgery eliminates the need for a rib-cutting incision, the risk of clinically significant PPSP still exists in 20–40% of patients.[3] Because no effective modality of prevention has been found, patients with PPSP continue to bear its consequences.

Physical and emotional suffering can lead to chronic pain and ultimately poor quality of life.[4] Surgical injury results in peripheral and central sensitization.[5] As central sensitization develops, pain signaling enhancement leads to uncoupling of pain stimulus and response (no stimulus or minimal stimulus can elicit a significant pain response). Central to those changes are the release of glutamate and its action on α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl4-isoxazolepropionic acid and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors.[5,6] Many of these changes can be potentially altered by NMDA antagonists.[7]

Emerging evidence also supports the role of inflammatory-immune cascades in the development of neuropathic pain, even in the absence of a clinically observable nerve injury.[8] Thoracic surgery is major organ surgery and results in significant inflammatory and immune responses.[9] Corticosteroids can neutralize those inflammatory-immune responses and hence modify the development and perception of PPSP.[10-11]

Study Interventions

Ketamine is a potent anesthetic and analgesic. It acts by blocking NMDA receptors in a noncompetitive fashion. At low doses, it has several perioperative benefits. At a dose of 1–6 μg/kg/min, it can have antihyperalgesic effects without significant cardiovascular and respiratory adverse effects.[12] The psychomimetic adverse effects are noted usually with a higher dose of ketamine (>2.5 μg/kg/min).[13-14] A recent Cochrane review observed a small but statistically important signal in its potential to decrease the chances of PPSP, both at 3 and 6 months, when used for a duration of more than 24 hours.[15] However, parenteral administration of ketamine is limited in some locations by the requirement for increased or enhanced monitoring.

Memantine is a moderate-affinity, uncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist that blocks the sustained activation of the receptor by glutamate that may occur under pathologic conditions. Memantine rapidly leaves the NMDA receptor channel during normal physiological activation. It is 100% bioavailable after an oral dose, undergoes minimal metabolism, and exhibits a terminal elimination half-life of 60–80 hours.[16] Although it is presently approved for use in Alzheimer disease, its effects on preventing pain have been studied in both animal and human studies.[17-18] However, most existing studies are preliminary and small.

Steroids are potent anti-inflammatory agents and can affect both inflammatory and immune pathways.[11-19] Among commonly used agents, dexamethasone is nearly five times as potent asmethylprednisolone, with a biological half-life of 36–72 hours.[11] Its potential to improve perioperative outcomes without significant harm have been recognized in abdominal, orthopedic, and other surgeries.[20–22] As identified in the Cochrane review, despite the potential for steroids to modify PPSP, overall, their effect on PPPS has not been well studied.[15]

Proposal

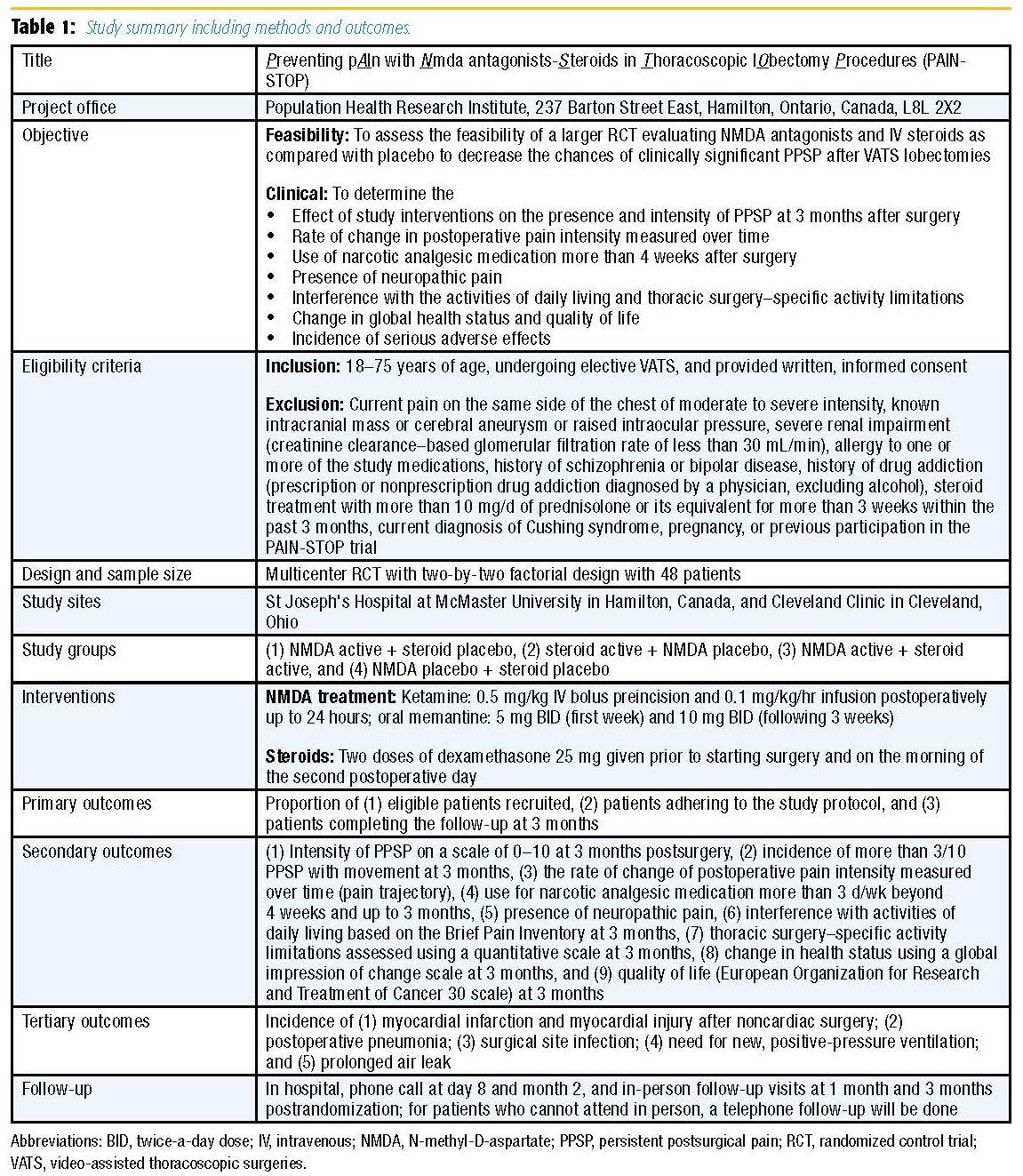

The PAIN-STOP pilot trial is a multicenter randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 48 patients. This RCT will use a two-by-two factorial design to evaluate NMDA antagonists versus placebo and intravenous dexamethasone versus placebo. Patients will be stratified based on site. Because the interventions work through different biologic pathways, we do not expect a negative interaction; hence, they are ideal drugs to study using a factorial design in a single trial to increase the efficiency by capitalizing on the resources required for an RCT.[23] Patients, health care providers, data collectors, outcome adjudicators, and investigators will all be blind to treatment allocation. The study methods and outcomes are highlighted in Table 1.

Strengths

- The study focuses on an important and challenging question that has been identified as a health priority.[24]

- The study interventions have sound biologic rationale and have been identified as potentially promising for preventing PPSP. More importantly, the interventions potentially cover the period of transition from acute to chronic pain, as suggested by the concept of preventive analgesia.[7,25]

- The factorial design allows for better efficiency in resources and cost, allowing for assessment of two different interventions.

- The clinical outcomes satisfy the definition of PPSP by ICD-1126 and include clinically important, patient-relevant outcomes.

- The design is a multicenter, international study that demonstrates the feasibility of a larger international trial with the potential for greater clinical translation and applicability.

- The study team includes experienced and well-recognized clinician investigators, research methodologists, and content experts.

- The study is being coordinated from the Population Health Research Institute at McMaster University in Hamilton, Canada, which is recognized as a leading research institute engaged in the conduct of large-scale, high-impact, randomized clinical trials.

Limitations

- The timing, dose, and duration of study interventions have been planned based on their biologic rationale and potential for clinical applicability, as a pragmatic study. However, the study will not be able to provide information on possible dosedependent effects or the impact of a different duration of study interventions.

Funding

- 2016 Carl Koller Memorial Research Grant award, ASRA, in July 2016 with USD 50,624.20

- Michael G. DeGroote Institute of Pain Research and Care seed grant, McMaster University, 2016 for CAD 30,000

Registration

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02950233?term=PAIn+STOP &draw=1&rank=1

Study Challenges

- Acquisition of memantine tablets at 5-mg and 10-mg strengths from a licensed supplier

- Obtaining approval of health regulatory authorities

- Collaborating and coordinating interdepartmental involvement (anesthesiologists, surgeons, pharmacy, nursing, clinical research) for the smooth conduct of the trial.

Study Updates

As of September 2017, the following updates indicate the study progress.

- The study has obtained approval of health regulatory authorities (Health Canada and the US Food and Drug Administration) for the use of investigational drugs.

- The study's memantine and placebo medications were encapsulated, labeled, and packaged.

- After approval from the ethics board, the study has been initiated at McMaster University in Hamilton, Canada, since May 2017.

- An ethics committee application at Cleveland Clinic will be submitted in October 2017.

- Ten patients have been recruited and completed their surgery.

- The study started at Cleveland Clinic in November 2017.

- Recruitment will be completed by April 2018 and follow-up completed by July 2018.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the support from our funding agencies and the entire PAIN-STOP investigating team.

References

- Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet 2006;367(9522):1618–1625.

- Wildgaard K, Ravn J, Kehlet H. Chronic post-thoracotomy pain: a critical review of pathogenic mechanisms and strategies for prevention. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2009;36(1):170–180.

- Gottschalk A, Cohen SP, Yang S, Ochroch EA. Preventing and treating pain after thoracic surgery. Anesthesiology 2006;104(3):594–600.

- Gureje O, Von Korff M, Simon GE, Gater R. Persistent pain and well-being: a World Health Organization Study in Primary Care. JAMA 1998;280(2):147–151.

- Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain 2011;152(3 suppl):S2–S15.

- Woolf CJ, Thompson SW. The induction and maintenance of central sensitization is dependent on N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor activation; implications for the treatment of post-injury pain hypersensitivity states. Pain 1991;44(3):293– 299.

- Himmelseher S, Durieux ME. Ketamine for perioperative pain management. Anesthesiology 2005;102(1):211–220.

- Ellis A, Bennett DL. Neuroinflammation and the generation of neuropathic pain. Br J Anaesth 2013;111(1):26–37.

- Amar D, Zhang H, Park B, Heerdt PM, Fleisher M, Thaler HT. Inflammation and outcome after general thoracic surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007;32(3):431–434.

- Zhang JM, An J. Cytokines, inflammation, and pain. Int Anesthesiol Clin 2007;45(2):27–37.

- Becker DE. Basic and clinical pharmacology of glucocorticosteroids. Anesth Prog 2013;60(1):25–31.

- Jouguelet-Lacoste J, La Colla L, Schilling D, Chelly JE. The use of intravenous infusion or single dose of low-dose ketamine for postoperative analgesia: a review of the current literature. Pain Med 2015;16(2):383–403.

- Mathews TJ, Churchhouse AM, Housden T, Dunning J. Does adding ketamine to morphine patient-controlled analgesia safely improve post-thoracotomy pain? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2012;14(2):194–199.

- Wang L, Johnston B, Kaushal A, Cheng D, Zhu F, Martin J. Ketamine added to morphine or hydromorphone patient-controlled analgesia for acute postoperative pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Can J Anaesth 2016;63(3):311–325.

- Chaparro LE, Smith SA, Moore RA, Wiffen PJ, Gilron I. Pharmacotherapy for the prevention of chronic pain after surgery in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;7:CD008307.

- Kumar S. Memantine: pharmacological properties and clinical uses. Neurol India 2004;52(3):307–309.

- Fayed N, Olivan-Blazquez B, Herrera-Mercadal P, et al. Changes in metabolites after treatment with memantine in fibromyalgia: a double-blind randomized controlled trial with magnetic resonance spectroscopy with a 6-month follow-up. CNS Neurosci Ther 2014;20(11):999–1007.

- Takeda K, Muramatsu M, Chikuma T, Kato T. Effect of memantine on the levels of neuropeptides and microglial cells in the brain regions of rats with neuropathic pain. J Mol Neurosci 2009;39(3):380–390.

- Rhen T, Cidlowski JA. Antiinflammatory action of glucocorticoids—new mechanisms for old drugs. N Engl J Med 2005;353(16):1711–1723.

- Lunn TH, Kehlet H. Perioperative glucocorticoids in hip and knee surgery— benefit vs. harm? A review of randomized clinical trials. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2013;57(7):823–834.

- Srinivasa S, Kahokehr AA, Yu TC, Hill AG. Preoperative glucocorticoid use in major abdominal surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Ann Surg 2011;254(2):183–191.

- Turan A, Sessler DI. Steroids to ameliorate postoperative pain. Anesthesiology 2011;115(3):457–459.

- Whelan DB, Dainty K, Chahal J. Efficient designs: factorial randomized trials. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012;94(suppl 1):34–38.

- International Association for the Study of Pain. IASP sponsors global year against pain after surgery. January 19, 2017. Available at: https://www.iasp-pain.org/ files/2017GlobalYear/News Release for 2017 Global Year.pdf. Accessed September 28, 2017.

- Katz J, Seltzer Z. Transition from acute to chronic postsurgical pain: risk factors and protective factors. Expert Rev Neurother 2009;9(5):723–744.

- Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, et al. A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain 2015;156(6):1003–1007.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top