How to Build a Block Room: A Canadian Perspective

The “block room”—a dedicated space outside of operating theaters for performing regional anesthesia—has no established history of inception. One of its earliest official descriptions, some 34 years ago, came as a result of a then-“alarming” dearth in regional anesthesia education.[1] With the rapid growth of ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia in the past decade, many centers have established a block room setup to promote efficiency, education, research, and patient experience when performing regional anesthesia.

Efficiency Benefits of a Block Room Model

One of the biggest barriers to providing regional anesthesia is time. Without a block room setup, nerve blocks are most commonly performed in operating rooms (ORs) prior to commencement of the surgery. Any increase in nonoperative time is considered inefficient.

Parallel processing with the use of a block room has been shown to reduce preprocedure OR time in upper-extremity surgeries by 21 minutes or the median turnover time from 54 to 15 minutes.

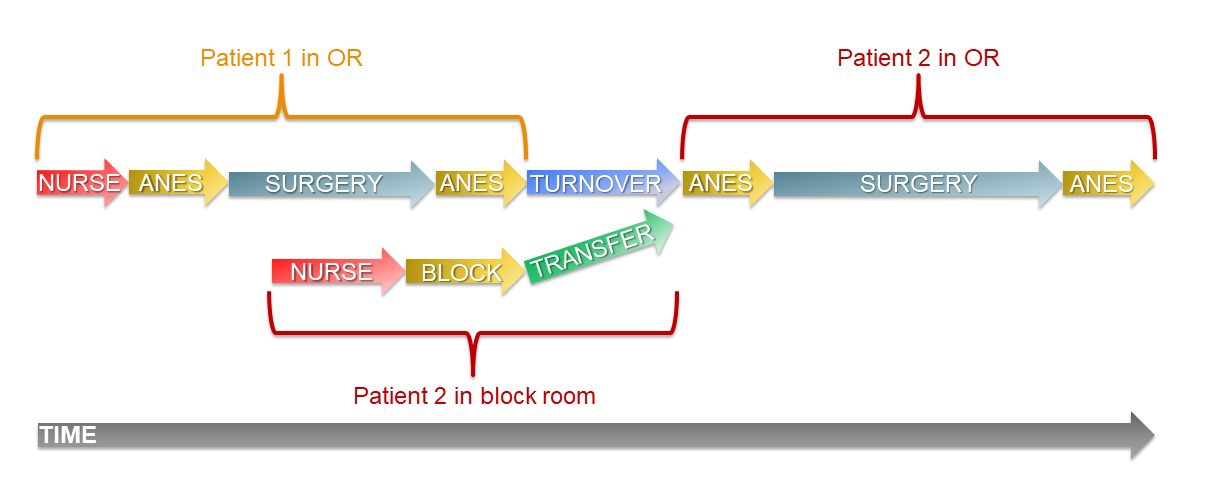

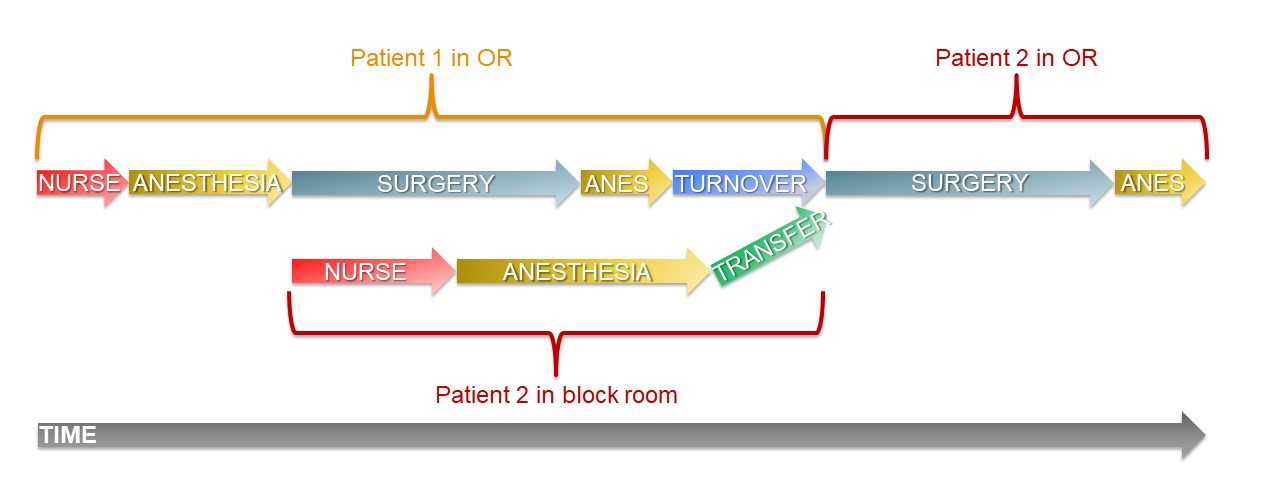

A block room overcomes that issue by allowing for a parallel-processing concept (see Figure 1). With two physical spaces dedicated for one surgeon’s list (the OR and the block room), anesthetic procedures for a subsequent patient can occur while the first patient is undergoing surgery. By the time the first patient leaves the OR, most (unless the patient is also undergoing general anesthesia) of the anesthesia-related procedures would have been completed in the block room, thus minimizing or eliminating anesthesia-related time spent in the OR.

Parallel processing with the use of a block room has been shown to reduce preprocedure OR time in upper-extremity surgeries by 21 minutes[2] or the median turnover time from 54 to 15 minutes (Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Department of Anaesthesia, unpublished data, 2005). Similarly, the introduction of a block room reduced anesthetic preparation time by 19 minutes when thoracic epidural anesthesia was employed.[2] The institution of a block room in an orthopedic hospital in Toronto performing lower-extremity arthroplasties reduced the overall OR time (including turnover time) by 18% and allowed for an extra case per room per day (Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Department of Anaesthesia, unpublished data, 2005). Another hospital in the United Kingdom was performing 25 blocks a week in the OR, and by instituting a block room, it reduced anesthetic time to allow for an average of one extra case per day.[3] However, depending on the case load and type of procedures, the efficiency benefit of a block room may not always offset the costs involved.

Cost Benefits of a Block Room Model

Studies have estimated that the cost of OR time ranges from $36 to $62 per minute but that reducing OR time alone would not greatly reduce the overall cost of an operation, per se, because of other indirect costs.[4],[5] However, other cost reductions include recovery room stay, hospital stay, and whether a regional technique reduces the likelihood of an intensive care unit admission. Of course, setting up a block room has additional initiation costs such as materials, the need for additional ancillary personnel, and extra space. Prior to making a business case, perform a cost-benefit calculation with hospital administration or accounting that considers the hospital case load and type and the availability of regional anesthesia–trained anesthesiologists.

Education Benefits of a Block Room Model

Block rooms allow for a central area where all regional anesthesia activities and personnel congregate. Experts can impart their knowledge on larger numbers of trainees who will potentially be involved in a higher number of regional procedures.[6],[7] This is obviously beneficial in academic health centers with anesthesia residents and fellows and may promote research activities. Even in nonteaching institutions, a block room setup can facilitate continued medical education for anesthesiologists looking to improve their regional anesthesia skills.

Teaching may be more effective in an arena with diminished time pressure that offers more opportunity for learners to participate while encouraging new ideas and techniques.[1],[2]

Figure 1a: Parallel processing for patients who have both regional and general anesthesia.

Figure 1b: Parallel processing for patients who have only surgical nerve block.

Patient Benefits of a Block Room Mode

In our experience, the number of nerve blocks performed has increased since the introduction of a block room. For example, our successful thoracic epidural insertion rate has increased by 26%. The ability to offer more regional blocks when indicated can lead to improved perioperative outcomes such as reduced recovery room and hospital length of stay and fewer readmissions.[8]

A block room can also provide a better patient experience during the actual regional block procedure. When patients enter an OR, they encounter myriad surgical equipment and multiple personnel preparing for surgery. Such an environment provides little privacy and may lead to increased patient anxiety. During a block room trial at one of our institutions, patients were surveyed about their experience in the block room. Compared with baseline, patients reported better preprocedure explanations with the block room model as well as better satisfaction overall.[4]

Furthermore, the block room has the potential to be a significant part of the anesthetic perioperative care model. If we reimagine the block room as an assessment and preoperative care unit, it can become much more than a place for regional anesthesia. An adequately equipped block room with appropriately trained staff can be used to perform all kinds of anesthesia procedures, such as point-of-care ultrasound assessments for semi-urgent patients, potentially altering management and postoperative care plans.

An anecdote from our block room is worth considering. A patient scheduled for ankle surgery complained of calf pain in the block room, and a bedside ultrasound of the popliteal vein and femoral veins found a deep vein thrombosis. The diagnosis may have happened without a block room, yet it illustrates the potential for a block room to go beyond nerves and needles.

From Planning to Implementation: The Logistics of Setting up a Block Room

Because of institutional differences, block room setups are not easily directly transferred from one hospital to another without modifications. To establish a block room setup that fits your local needs, we suggest that a quality improvement project be conducted using the Plan-Do-Study-Act Model as a guide.[5]

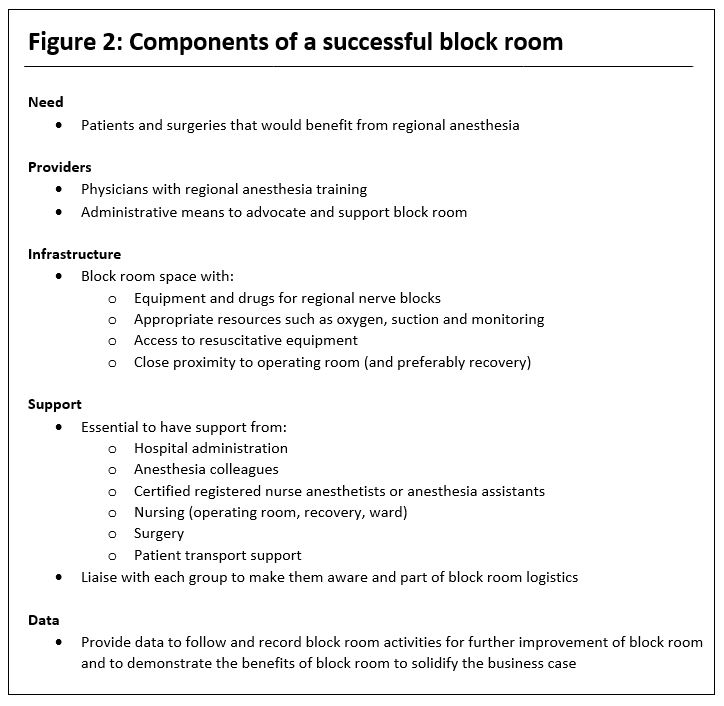

We recently set up a second block room in the main site of one of our institutions. This site treats a large trauma and oncology population. With the support of hospital administration and nursing teams, we set up a two-bay block room using existing OR infrastructure, labor resources, and equipment. The block room was sited in a part of the recovery room that was not being used but had monitors, oxygen supply, and suction. We used a set of portable shelves to house the equipment and the ultrasounds that were already part of the OR pool. We staffed the block room with an anesthesia fellow and a consultant (as the block room coordinator) from the OR who was booked with a senior trainee. Although we do rotate residents through our block room, the trainee is not booked on a regional rotation, which allows the coordinator some latitude in movement on busy days. Ancillary staff consists of a circulating nurse from the patient’s OR to check the patient when he or she arrives and an anesthesia assistant who floats between the ORs and the block room. The setup resulted in very little real cost to the hospital because most of the process just required shifting existing materials and labor. The detailed components of a successful block room are further illustrated in Figure 2.

Every day, the block room coordinator evaluates the following day’s list and selects suitable patients for the block room. Block room service time starts 60 minutes prior to the actual OR start time for the first case. For subsequent cases, the block room coordinator liaises with various ORs and checks the urgent list for any block candidates. Although the process is labor intensive, it allows for additional patients to be brought into the block room well in advance of their procedure and complete the block with very little time pressure.

Figure 2: Components of a successful block room.

During a trial period, we started a block room database using a simple electronic spreadsheet that identified each procedure, time spent in the room, time spent doing the actual block, and the time the patient went to the OR. During down time between blocks, the staff anesthetist or fellow enters the data into the computer from the block room sheet that anesthesia assistants complete for each procedure. However, the hospital created a patient-tracking system for all the ORs that also serves as a database. We will be switching to this system because it automatically creates a patient encounter, can be completed using drop-down menus, and will follow patients longitudinally throughout their hospital stay.

In the pilot project’s first month, we had more than 70 patients in our block room and reduced OR time by 15–20 minutes per patient, a positive impact because our hospital has been dealing with significant labor costs related to overtime. In some cases, patients would not have received a block if a designated block room did not exist, and that time savings would not apply. However, our group contended that the length of stay in recovery would be reduced or eliminated with the increased number of regional techniques performed, which has the potential to affect patient flow and ultimately decrease hospital costs. With these data, hospital management realized that the benefits of a block room justified the added costs and agreed to fund an anesthesia assistant position for 5 working days per week.

Conclusion

Block rooms have many benefits in terms of patient quality of care, health care education, efficiency, and potentially cost savings for hospitals. Because they may not be useful in every hospital setting, a careful assessment of the cost-benefit ratio should be carried out before initiation. The design and implementation of an institution-specific block room setup should be multidisciplinary and data continuously collected to confirm the proposed benefits and refine the setup over time.

References

- Rosenblatt RM, Shal R. The design and function of a regional anesthesia block room. Reg Anesth 1984;9:12–16.

- Gleicher Y, Singer O, Choi S, McHardy P. Thoracic epidural placement in a preoperative block area improves operating room efficiency and decreases epidural failure rate. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2017;42:649–651.

- Chazapis M, Kaur N, Kamming D. Improving the peri-operative care of patients by instituting a ‘block room’ for regional anaesthesia. BMJ Open Qual 2014;3:u204061.w1769.

- Crnic A, McCartney CM, McConnell M, Wong PB. A procedure room for regional and neuraxial anesthesia: effects on OR efficiency and patient satisfaction [abstract A2086]. Presented at: Anesthesiology Annual Meeting; October 2017; Boston, MA.

- Berwick DM. A primer on leading the improvement of systems. BMJ 1996;312:619–622.

- Martin G, Lineberger CK, MacLeod DB, et al. A new teaching model for resident training in regional anesthesia. Anesth Analg 2002;95:1423–1427.

- Richman JM, Stearns JD, Rowlingson AJ, Wu CL, McFarland EG. The introduction of a regional anesthesia rotation: effect on resident education and operating room efficiency. J Clin Anesth 2006;18:240–241.

- Liu SS, Strodtbeck WM, Richman JM, Wu CL. A comparison of regional versus general anesthesia for ambulatory anesthesia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesth Analg 2005;101:1634–1642.