Peripheral Nerve Stimulation for Extended Acute Pain Management after Amputation: The Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center Experience

Cite as: O'Conor K, Barre S, Adhikary S. Peripheral nerve stimulation for extended acute pain management after amputation: the Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center experience. ASRA Pain Medicine News 2024;49. https://doi.org/10.52211/asra050124.009.

Introduction

Limb loss is becoming increasingly prevalent in the United States. In 2005, an estimated 1.6 million people were living with limb loss. This number is expected to increase to 3.6 million by 2050.1 Post amputation pain affects 95% of amputees and includes phantom limb pain, phantom limb sensation, and residual limb “stump” pain.2 Phantom limb pain and phantom limb sensations affect greater than 80% of post amputation patients.3 More than one third of these patients describe this pain as severe.2,4

At Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, we frequently use peripheral nerve stimulation (PNS) for the management of post-amputation pain. Data concerning the efficacy of PNS in treating amputation is limited. However, there are small studies that demonstrate its ability to decrease residual limb pain, opioid consumption, and phantom limb pain.6 Recently, there have been case reports and case series using hybrid techniques of continuous local anesthetic infusion through a nerve block catheter, combining it with brief perineural stimulation with positive results for postoperative analgesia.7-10 An increased interest has been placed on the use of neuromodulation via perineural electrical stimulation in the acute pain setting.10,11 At our institution, we commonly place PNS immediately after amputation, and we would like to outline our experience and patient pathway.

Patient Population and Pain Control Pathway

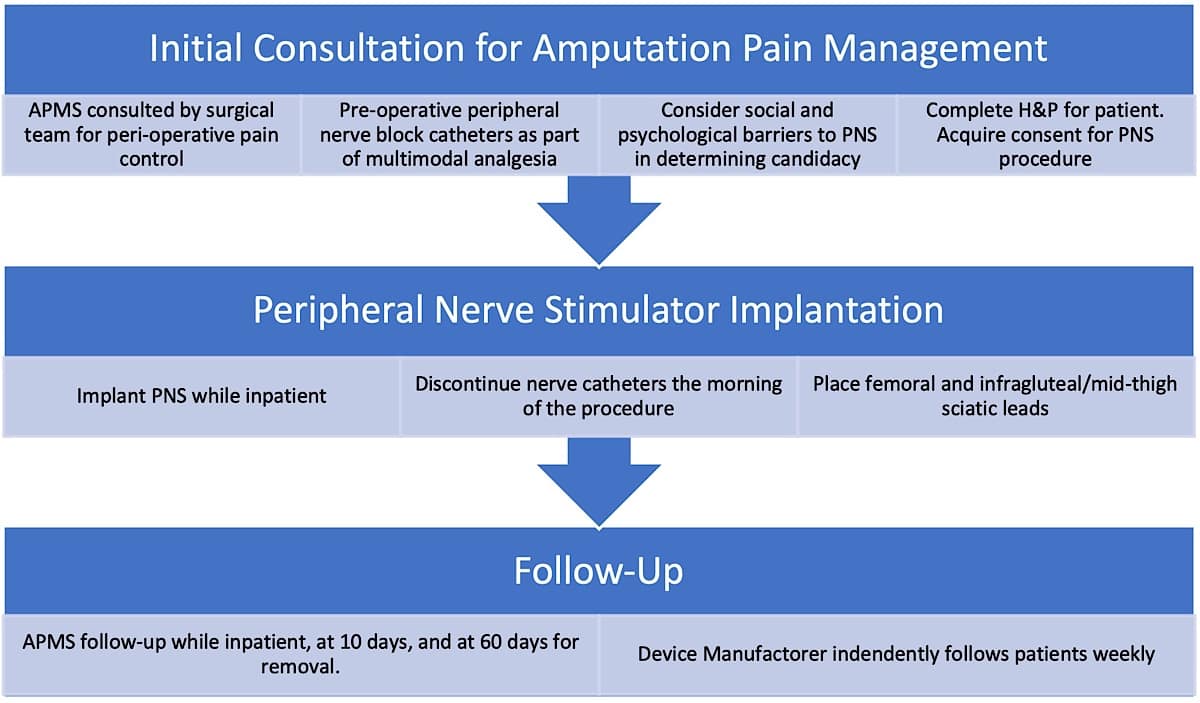

At Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, the most common types of amputations are below-knee-amputation (BKA) and above-knee-amputation (AKA). The most common indications for surgery are infection and ischemia. Cancer and trauma are much less frequent. When patients are scheduled for primary amputation or for surgical revision, the Acute Pain Medicine Service (APMS) is consulted by the surgical team for peri-operative pain management (Figure 1).

Preoperative peripheral nerve block catheters are favored although in certain cases they are placed postoperatively. For BKA, patients receive sciatic and saphenous nerve continuous catheters. For AKA, patients receive femoral or fascia iliaca catheters as well as sciatic nerve catheters. The APMS team provides postoperative recommendations regarding multimodal analgesia and additionally manages the peripheral nerve catheter. Timing of PNS placement is decided in collaboration with the surgical team. We recommend placing the PNS 2 to 7 days postoperatively while the patient is still hospitalized. In certain cases, patients return for the procedure as outpatients.

Prior to placing a PNS, the physician performs a detailed history and physical examination and reviews medications and allergies. Factors that may make a patient ineligible for the procedure include significant social and psychological barriers that may prevent appropriate patient follow-up. Inability to complete follow-up during treatment and for removal of device leads is a potential safety concern. Patients must have a support network if they are unable to complete dressing changes or battery replacements on their own. PNS is often not offered to patients whose circumstances interfere with their ability to complete treatment. As the nerves we target are generally superficial, concurrent use of anticoagulant or antiplatelet medications is not a contraindication to the placement of a peripheral nerve catheter.

Equipment and Preparation

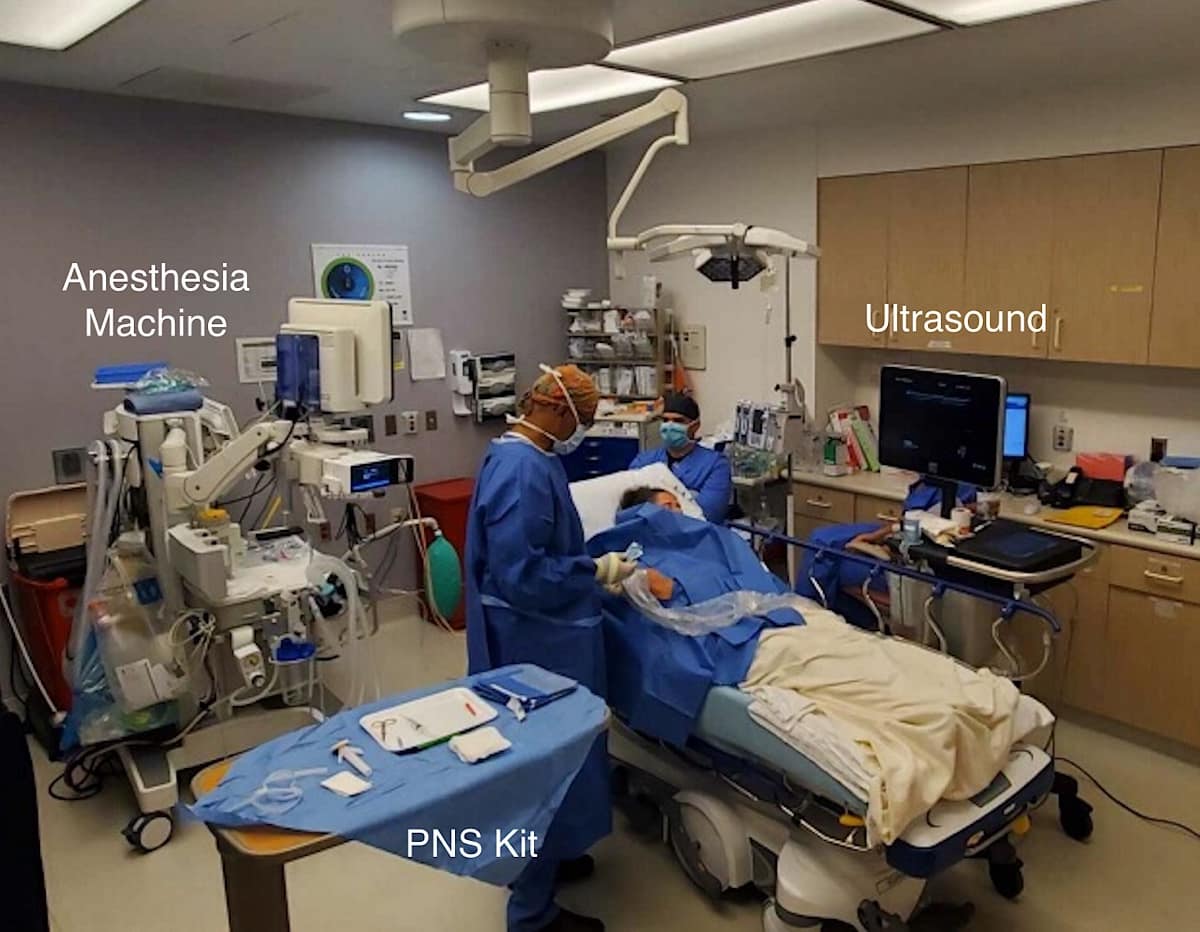

Patients are brought to a procedure room and a separate anesthesia team administers anxiolysis, most commonly with fentanyl and/or midazolam (Figure 2). PNS is performed with real time ultrasound guidance, preferably using a high-frequency (10-15 MHz) linear-array transducer for patients having a normal body habitus. For the PNS, we use the SPR Therapeutics SPRINT extensa® System. This system is currently Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for symptomatic relief of post-surgical and post-traumatic acute pain as well as symptomatic relief of post-operative pain.

Scanning and Lead Placement Technique

Patients with BKA and AKA receive femoral and sciatic (infragluteal/mid-thigh approach) PNS leads. The femoral approach leads to a more comfortable lead placement compared to placement at the adductor canal. Unlike peripheral nerve blocks with local anesthetic, motor blockade or muscle weakness is not a concern with PNS.

For femoral nerve lead placement, the patient is placed in the supine position. The ultrasound probe is placed transversely at the inguinal crease over the femoral artery. An in-plane technique is used for needle insertion (Figure 3). The skin and muscle are first infiltrated with 1% lidocaine, ensuring that the local anesthetic is not injected close to the nerves as this may interfere with stimulation testing. The percutaneous sleeve containing the stimulating probe is advanced towards the femoral nerve (Figure 4).

Stimulation is tested to make sure that the patient feels a comfortable sensation in the distribution of the femoral nerve within a range of intensity of 20-70 on the device. The intensity value does not have units, but only a range of 0-100. It is a combination of amplitude (mA) and pulse duration (μs.) A comfortable stimulation at an intensity range of 20-70 confirms proper needle location. Submaximal stimulation provides room for uptitration later in the treatment course. Scar formation around the wire lead as the body’s response to a foreign object provides additional resistance to the electrical stimulation, requiring higher intensity to achieve clinical effect. The stimulating probe is then removed while the sheath remains in place. Next, the lead with its introducer unit is placed 5-15 mm from the nerve. The lead introducer is removed leaving the lead in place. A final test of stimulation level is conducted. The lead is fixed in place with Dermabond and an adhesive covering bandage.

Preoperative peripheral nerve block catheters are favored although in certain cases they are placed postoperatively.

For infragluteal/midthigh sciatic placement, the patient is placed in the lateral position with the hip flexed and the residual limb supported by a stack of blankets. The ultrasound probe is placed transversely over the posterior thigh, and the sciatic nerve is identified (Figure 5). The positioning of the lead is more distal than a traditional infragluteal approach for patient comfort and to allow lead connection to the pulse generator. An in-plane technique is used (Figure 6). The steps for lead placement are the same as described above for femoral nerve lead placement. After both leads have been inserted, they are connected to the pulse generator secured on the anterolateral thigh (Figure 7).

After the PNS is successfully inserted, the device is programmed according to manufacturer guidance although patients are able to adjust the settings to optimize pain control.

Follow-up and Removal

The APMS team follows PNS patients while they remain hospitalized. Following hospital discharge, they are called on or before 10 days following the procedure and again for device lead removal. Representatives from the device manufacturer complete independent patient follow-up as part of their own corporate mandate immediately after device placement at 24 hours post-placement and then weekly until lead removal. They are not part of the formal care team. However, if any problems are identified during one of these follow-up encounters by the device representative, the problem is communicated to a member of our APMS team for further management recommendations.

The patients return to our anesthesia clinic 60 days after PNS placement for lead removal. Lead removal occurs within the office suite at the anesthesia clinic. A potential complication of device removal is lead fracture, in which a portion of the device lead is retained within the patient. In this case, the fractured lead is typically left in place, and patients are counseled about restrictions on undergoing future magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) testing. Generally, the patients will need lesser strength MRI machines to be used for their future MRIs. Further details regarding MRI restrictions can be found in the manufacturer literature.

Billing Considerations

These procedures are completed in the inpatient setting as reimbursement and pre-authorization can be done more quickly as compared to the outpatient setting. The CPT code we used for the procedure is 64555. Available diagnosis codes (ICD-10) for PNS placement include: other acute postprocedural pain (G89.18), other chronic postprocedural pain (G89.28), phantom limb syndrome with pain (G54.6), and any other complications of amputation stump (T87.89). Coverage for procedures varies based on payer type.

We expect that as neuromodulation technology advances and other manufactures produce similar devices, the costs to patients will decrease. Alternative methods of peripheral nerve stimulation exist, including perineural stimulating catheters and permanent placement of spinal cord stimulators and dorsal root ganglion stimulators. Our described method of neuromodulation is for longer duration than perineural stimulating catheters and more amenable to the treatment of acute pain compared to spinal cord or dorsal root ganglion stimulation.

Conclusion

Limb amputation is becoming increasingly prevalent in the United States. After such surgery, patients commonly suffer from post-amputation pain and decreased quality of life. There is an increased interest in using electrical perineural stimulation for neuromodulation. At Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, we are using peripheral nerve stimulation after amputation for extended acute post-amputation pain management. While the traditional role of the acute pain medicine team has only been in the inpatient setting, with PNS, we are hoping to provide patients with pain relief as they move from the inpatient into the outpatient setting. Similar to other previous experience of perineural stimulation after amputations at other institutions as referenced above, anecdotally, we have seen positive results in the patients that we have treated, and outcomes studies are ongoing.

References

- Ziegler-Graham K, MacKenzie EJ, Ephraim PL, et al. Estimating the prevalence of limb loss in the United States: 2005 to 2050. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008;89:422-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2007.11.005

- Ephraim PL, Wegener ST, MacKenzie EJ, et al. Phantom pain, residual limb pain, and back pain in amputees: results of a national survey. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 200;86:1910-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2005.03.031

- StankeviciusA, WallworkSB, SummersSJ, et al. Prevalence and incidence of phantom limb pain, phantom limb sensations and telescoping in amputees: a systematic rapid review. Eur J Pain 2021;25:23–38.https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1657

- Clark RL, Bowling FL, Jepson F, et al. Phantom limb pain after amputation in diabetic patients does not differ from that after amputation in nondiabetic patients. Pain 2013;154:729-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2013.01.009

- Albright-Trainer B, Phan T, Trainer RJ, et al. Peripheral nerve stimulation for the management of acute and subacute post-amputation pain: a randomized, controlled feasibility trial. Pain Manag 2022;12:357-69. https://doi.org/10.2217/pmt-2021-0087

- Gilmore C, Ilfeld B, Rosenow J, et al. Percutaneous peripheral nerve stimulation for the treatment of chronic neuropathic postamputation pain: a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med2019;44:637-45. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2018-100109

- Ip VHY, Sondekoppam RV, Tsui BCH. Augmenting conventional regional nerve block with peripheral neuromodulation using a perineural stimulating catheter. Can J Anaesth 2021;68(5):740-1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-021-01917-3

- Miser J, Seering M, Sondekoppam RV, et al. Single perineural catheter for hybrid technique of combined peripheral nerve stimulation and regional local anesthetic nerve block to manage phantom limb pain: time to jump on the neuromodulation bandwagon? Reg Anesth Pain Med 2022;47(4):277-8. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2021-103220

- Sondekoppam RV, Ip V, Tsui BCH. Feasibility of combining nerve stimulation and local anesthetic infusion to treat acute postamputation pain: a case report of a hybrid technique. A A Pract 2021;15(6):e01487. https://doi.org/10.1213/XAA.0000000000001487

- Ip VHY, Kotteeswaran Y, Prete S, et al. Neuromodulation using a hybrid technique of combined perineural local anesthetic and nerve stimulation in six challenging clinical scenarios. Can J Anaesth 2023;70(2):273-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-022-02373-3

- Tsui BCH, Gupta RK. Role of neuromodulation in acute pain settings. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2023;48(6):338-42. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2022-103837