Trigeminal Neuralgia

Author

Samer Narouze, MD, MSc

Program Director, Pain Medicine Fellowship

Cleveland Clinic

Cleveland, OH

Chairman, Pain Management Department

Summa Western Reserve Hospital

Cuyahoga Falls, OH

Introduction

Trigeminal neuralgia is the most common form of facial neuropathic pain in elderly people with an annual incidence of 4-5 new patients per 100,000. Trigeminal neuralgia is more prevalent in women than men in a ratio of 1.5:1.[1] There are 2 types of trigeminal neuralgia. They are: 1) classical trigeminal neuralgia and 2) symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia.

A. Classical Trigeminal Neuralgia

Classical trigeminal neuralgia was previously called tic douloureux, primary trigeminal neuralgia, and idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia.

Pathophysiology

Although the actual pathophysiology of trigeminal neuralgia remains undetermined, most patients are found to have compression of the trigeminal nerve root by tortuous or aberrant vessels noted in posterior fossa exploration surgery and magnetic resonance imaging.

Clinical Presentation

Trigeminal neuralgia is a unilateral disorder characterized by brief electric shock-like pains, abrupt in onset and termination, limited to the distribution of one or more divisions of the trigeminal nerve. Pain is commonly evoked by trivial stimuli including washing, shaving, smoking, talking and/or brushing the teeth (trigger factors) and frequently occurs spontaneously.

Small areas in the nasolabial fold and/or chin may be particularly susceptible to the precipitation of pain (trigger areas). The pains usually remit for variable periods.[2]

Classical trigeminal neuralgia usually starts in the second or third divisions (V2-V3), affecting the cheek or the chin. In <5% of patients the first division (V1) is affected. (Table 1)

| (Adopted from reference 1 with modifications) | |

| V1 only | 4% |

| V2 only | 17% |

| V3 only | 15% |

| V1 + V2 | 14% |

| V2 + V3 | 32% |

| V1 + V2 + V3 | 17% |

The pain is strictly unilateral, right side more than the left with a ratio of 3:2. It rarely occurs bilaterally, in which case a central cause such as multiple sclerosis must be considered especially in young patients. Between paroxysms the patient is usually pain free but a dull continuos pain may persist in some long-standing cases. Following a painful paroxysm there is usually a refractory period during which pain cannot be triggered. The pain often evokes spasm of the muscle of the face on the affected side (tic douloureux).

Neurological examination is essentially normal in patients with idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia. This is different from patients with secondary trigeminal neuralgia where there are some neurological deficits. In this case trigeminal neuralgia is a symptom of another disease e.g. multiple sclerosis or cerebellopontine angle neoplasm.

Diagnosis

The clinical diagnostic criteria are:

- Paroxysmal attacks of pain lasting from a fraction of a second to 2 minutes, affecting one or more divisions of the trigeminal nerve and fulfilling criteria B and C

- Pain has at least one of the following characteristics:

- 1. Intense, sharp, superficial or stabbing

- 2. Precipitated from trigger areas or by trigger factors

- Attacks are stereotyped in the individual patient

- There is no clinically evident neurological deficit

- Not attributed to another disorder

Imaging Studies

MRI is essential to identify any neurovascular compression (idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia) and to rule out other pathology e.g. multiple sclerosis, posterior fossa tumors (secondary trigeminal neuralgia).

Differential Diagnosis

The list of differential diagnosis is extensive including all unilateral headache and facial neuropathic pain disorders. Two common facial pain syndromes need to be excluded. First is multiple sclerosis should be always considered, especially in bilateral cases and young patients. Second is post herpetic trigeminal neuralgia which is a major cause of secondary trigeminal neuralgia. Contrary to idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia, it usually affects V1 more than V2 or V3. Usually there is a history of herpes zoster infection and/or rash.

B. Symptomatic Trigeminal Neuralgia

Pain from symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia is indistinguishable from classic trigeminal neuralgia but caused by a demonstrable structural lesion other than vascular compression.[1]

Diagnosis

The clinical diagnostic criteria are:

- Paroxysmal attacks of pain lasting from a fraction of a second to 2 minutes, with or without persistence of aching between paroxysms, affecting one or more divisions of the trigeminal nerve and fulfilling criteria B and C

- Pain has at least one of the following characteristics:

- Intense, sharp, superficial or stabbing

- Precipitated from trigger areas or by trigger factors

- Attacks are stereotyped in the individual patient

- A causative lesion, other than vascular compression, has been demonstrated by special investigations and/or posterior fossa exploration.

Treatment

Pharmacological Therapy

Classic trigeminal neuralgia is usually responsive, at least initially, to pharmacotherapy. (Table 2)

The first medication of choice is carbamazepine or oxycarbamazepine.

The second medication of choice is Baclofen. Other medications which can be tried, although there is no clinical evidence for their efficacy, are other anticonvulsants e.g. gabapentin, pregabalin.[1][3]

| Medication | Dosage | Time to pain relief |

|---|---|---|

| (Adopted from reference 1 with modifications) | ||

| Carbamazepine | 400-800 mg/d | 24-48 h |

| Oxycarbamazepine | 900-1800 mg/d | 24-72 h |

| Phenytoine | 300-500 mg/d | 24-48 h |

| Baclofen | 40-80 mg/d | ? |

| Clonazepam | 1,5-8mg/d | ? |

| Valproate | 500-1500 mg/d | weeks |

| Lamotrigine | 150-400 mg | 24 h |

| Gabapentine | 900-3600 mg/d | 1 week |

Interventional Procedures

When pharmacological treatment becomes ineffective or intolerable, interventional options are considered.

A. Surgery

Surgical Microvascular Decompression (MVD)

The vessels in contact with the trigeminal root entry zone are coagulated or separated from the nerve using an inert sponge.[4]

B. Percutaneous Procedures

Percutaneous Gamma Knife

This stereotactic radiation therapy procedure is non-invasive and allows high dose irradiation of a small section of the trigeminal nerve. This leads to non-selective damage of the Gasserian ganglion.[5]

Percutaneous Balloon Microcompression

The Gasserian ganglion is compressed by a small balloon, which is percutaneously introduced through a needle into the Meckelís cavity. This leads to ischemic damage of the ganglion cells. The technique may be more suitable for treatment of V1 trigeminal neuralgia of the first branch as the corneal reflex tends to remain intact.[6][7]

Percutaneous Glycerol Rhizolysis

Under fluoroscopy, with the patient in the sitting position and the head flexed, the needle is introduced into the trigeminal cistern, visualized by X-ray. Contrast agent is then injected to determine the size of the cistern before an equal volume of glycerol is injected after aspiration of the contrast agent.[8]

Percutaneous Radiofrequency Thermocoagulation of the Gasserian Ganglion

This is usually considered for elderly patients who have a high risk for surgical MVD. The outcome may be less favorable than MVD, but it is less invasive with lower morbidity and mortality rates.[9]

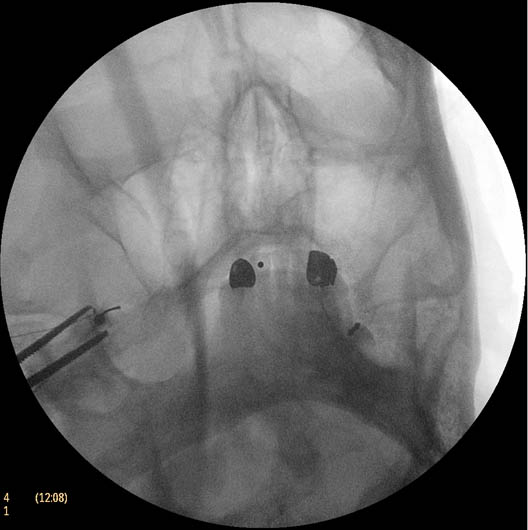

Figure 2. Trigeminal ganglion thermal radiofrequency ablation; oblique submental view showing the needle tip inside the foramen ovale

Figure 3. Trigeminal ganglion thermal radiofrequency ablation; lateral view showing the needle going through the foramen ovale with the needle tip overlying the petrous bone

This procedure is usually performed under monitored anesthesia care (MAC) with propofol or dexmedetomidine. The patient is in the supine position with the head inside the C-arm. After rotating the C-arm to obtain a submental view, the C-arm is slightly tilted to the affected side (oblique submental view), till the foramen ovale is best visualized (Figure 2). It usually projects medially to the mandibular process.

The point of the needle is about 2 cm lateral to the corner of the mouth on the ipsilateral side. A 100 mm 22 G radiofrequency needle with a 2 mm active tip is then advanced towards the foramen ovale under real time fluoroscopy first in the AP submental view and then in the lateral view.

It is important to place a finger in the mouth to prevent or detect oral mucosa penetration. Once the needle is inside the foramen ovale, testing stimulation is started. When motor stimulation (masseter muscle, V3) is encountered, the needle needs to be slightly advanced into the foramen carefully about 2 mm to stimulate V2. In the lateral view, the needle tip should be deep into the foramen, overlying the petrous bone(Figure 3).

The patient is then allowed to wake up and sensory stimulation can be carried out with 50 Hz. Paresthesia should be felt between 0.05 V and 0.1 V in the painful areas. V3 stimulation is encountered superficial and lateral in the foramen, then V2, and V1 is the deepest towards the pons and more medially. After appropriate paresthesia, a 60o C thermo lesion is carried out for 60 seconds. The corneal reflex is tested as well as the treated dermatome for hypoesthesia. If intact, a second lesion is made at 65o C for 60 seconds and if there is still no hypoesthesia then a third lesion can be made at 70o C for another 60 seconds.

Pulsed Radiofrequency Ablation of the Gasserian Ganglion

Although it would seem a safer alternative than the commonly used thermal RFA, its efficacy is questioned in a randomized controlled study.[10]

Gasserian Ganglion Neuromodulation

Gasserian ganglion electric stimulation was reported either via a subtemporal craniotomy,[11] or a percutaneous approach.[12] Technical difficulties and lead migration are the main factors that this approach thus it is not widely used.

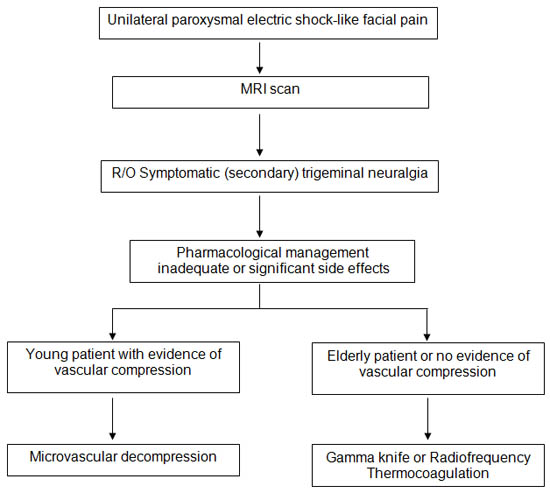

Choice of Treatment

There are few systematic reviews comparing various treatment approaches.[9][13-14] The first treatment of choice should always be conservative management. For those who failed pharmacological therapy, interventional management can be considered (Figure 1).[15] In general, younger patients with MRI evidence of vascular compression should be candidates for surgical MVD. The other minimally invasive procedures are generally considered to be less effective with higher relapse rate.

Figure 1. Algorithm for the management of trigeminal neuralgia

Complications

Several potential complications of Gasserian Ganglion block and neurolysis deserve mention. The gasserian (trigeminal) ganglion lies within the Meckelís cave, which is formed by a dura mater fold that surrounds the posterior two-thirds of the ganglion. The Meckelís cave contains CSF, so local anesthetic deposited in this area may spread to other cranial nerves and can potentially cause brain stem anesthesia.[16] Meticulous attention should be paid to avoid intravascular injection.[17] Negative aspiration is unreliable and injection of the contrast agent should be performed under real time fluoroscopy with digital subtraction, if available, prior to injection of the local anesthetic.

In a systematic review of ablative neurosurgical techniques for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia, Lopez et al.9 concluded that although radiofrequency thermocoagulation (RFT) seems to provide the highest rates of sustained complete pain relief, it is the technique associated with the greatest number of complications. In the analyzed series, 29.2% of the patients developed some complications, mostly transient, with RFT. The rate of complications from glycerol rhizolysis (GR) was 24.8%. Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) was the safest technique; only 12.1% of the patient experienced complications, mostly dysesthesias (Table 3).

Postoperative trigeminal sensory loss affects virtually all patients treated with RFT and it is considered a side effect rather than a complication. However in a prospective study, 30% of these patients may suffer from permanent sensory loss.[18]

| Radiofrequency Thermocoagulation | Glycerol Rhizolysis | |

|---|---|---|

| (Adopted from reference 9 with modifications.) | ||

| Complications rate | 29.2% | 24.8% |

| Masticatory weakness | 11.9% | 3.1% |

| Dysesthesia (severe) | 3.7% | 8.7% |

| Anesthesia Dolorosa | 1.6% | 2.3% |

| Corneal numbness | 9.6% | 8.1% |

| Keratitis | 1.3% | 2.1% |

| Cranial nerve deficits | 0.9% | 0.2% |

| Meningitis | 0.2% | 0.7% |

Summary

Trigeminal neuralgia is the most common form of facial neuropathic pain in the elderly. MRI is essential to identify any neurovascular compression (idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia) and to rule out other pathology e.g. multiple sclerosis, posterior fossa tumors (secondary trigeminal neuralgia). Interventional management is usually warranted after failure of conservative treatment.

References

- Rozen TD: Trigeminal neuralgia and glossopharyngeal neuralgia. Neurol Clin 2004;22:185-206.

- The international classification of headache disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalgia 2004;24:9-160.

- Wiffen P, Collins S, McQuay H, Carroll D, Jadad A, Moore A: Anticonvulsant drugs for acute and chronic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000:CD001133.

- Jannetta PJ, McLaughlin MR, Casey KF: Technique of microvascular decompression. Technical note. Neurosurg Focus 2005;18:E5.

- Young RF, Vermulen S, Posewitz A: Gamma knife radiosurgery for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg 1998;70 Suppl 1:192-199.

- Mullan S, Lichtor T: Percutaneous microcompression of the trigeminal ganglion for trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg 1983;59:1007-1012.

- Belber CJ, Rak RA: Balloon compression rhizolysis in the surgical management of trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurgery 1987;20:908-913.

- Hakanson S: Trigeminal neuralgia treated by the injection of glycerol into the trigeminal cistern. Neurosurgery 1981;9:638-646.

- Lopez BC, Hamlyn PJ, Zakrzewska JM: Systematic review of ablative neurosurgical techniques for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurgery 2004;54:973-982.

- Erdine S, Ozyalcin NS, Cimen A, Celik M, Talu GK, Disci R: Comparison of pulsed radiofrequency with conventional radiofrequency in the treatment of idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia. Eur J Pain 2007;11:309-313.

- Meyerson BA, Hakansson S: Alleviation of atypical trigeminal pain by stimulation of the gasserian ganglion via an implanted electrode. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 1980;30:303-309.

- Meglio M: Percutaneous implantable chronic electrode for radiofrequency stimulation of the gasserian ganglion: A perspective in the management of trigeminal pain. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1984:521-525.

- Spatz AL, Zakrzewska JM, Kay EJ: Decision analysis of medical and surgical treatments for trigeminal neuralgia: How patient evaluations of benefits and risks affect the utility of treatment decisions. Pain 2007;131:302-310.

- Tatli M, Satici O, Kanpolat Y, Sindou M: Various surgical modalities for trigeminal neuralgia: Literature study of respective long-term outcomes. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2008;150:243-255.

- van Kleef M, van Genderen WE, Narouze S, Nurmikko TJ, van Zundert J, Geurts JW, Mekhail N. Trigeminal neuralgia. Pain Pract 2009; 9(4): 252-9

- Murphy T: Somatic blockade of head and neck. In: Cousins M, Bridenbaugh P (eds): Neural Blockade: In Clinical Anesthesia and Management of Pain. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA, Lippencott-Raven, 1998, pp 489-514

- Narouze S. Complications of head and neck procedures. Techniques in Regional Anesthesia and Pain Management 2007; 11; 171-177

- Zakrzewska JM, Jassim S, Bulman JS: A prospective, longitudinal study on patients with trigeminal neuralgia who underwent radiofrequency thermocoagulation of the gasserian ganglion. Pain 1999;79:51-58.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top